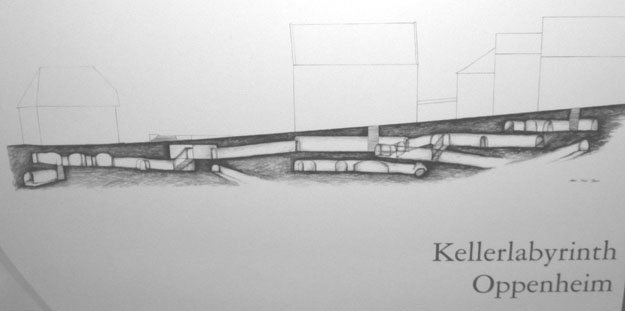

Centuries-old labyrinth lies hidden under Oppenheim’s streets, telling a story of war, wine, and rediscovery

A Town with Layers

Oppenheim sits peacefully on the Rhine River’s west bank. At first glance, it looks like any charming medieval town. Cobblestone streets wind past beer halls and a Gothic cathedral. But beneath those stones lies a vast secret: over 25 miles of underground tunnels.

This hidden network, known as the Kellerlabyrinth, runs deep below the surface. Some believe the tunnels may stretch beyond 124 miles. Many remain unexplored. Some may lead to private cellars under local homes.

Wilfried Hilpke, a tour guide for Oppenheim’s tourism office, has been guiding visitors through the tunnels for over a decade. “The town is practically honeycombed with cavities,” he says.

From Storage to Shelter

The tunnels have been around for centuries. Some sections date back as far as 700 A.D. Initially, they served a practical purpose—storing food and wine. Workers used simple tools to carve them out during the 1600s.

Trade was booming at that time. Residents needed extra storage and safer ways to move goods. The tunnels offered both.

Later, the tunnels became places of refuge. During the Thirty Years’ War, townspeople hid from invading Spanish troops underground. They even stored stained-glass windows from the Katharinenkirche cathedral to shield them from bombings.

Destruction and Disappearance

Oppenheim faced disaster in 1689. Louis XIV of France ordered its destruction during the War of Palatine Succession. The town burned. Its status as a free imperial city made it a target.

After the war, only a few hundred residents returned. They filled the tunnels with debris during rebuilding. The once-essential labyrinth slipped into memory and myth.

Rediscovery After a Storm

Then came the 1980s. During a heavy storm, a police car suddenly sank into the street. Underneath, a tunnel had collapsed. The forgotten network reemerged.

Why did it collapse? Moisture had seeped into the loess soil above the tunnels. Without ventilation, the earth became unstable.

Loess is fine, silt-like soil. Normally, it holds firm. But too much moisture weakens it. Beneath it lies limestone—soft enough to dig with a spoon, yet solid when dry. “A herd of buffalo could walk over it,” Hilpke says, brushing dust off a tunnel wall.

Five Levels of History

Today, tourists can walk through five levels of the labyrinth. The tunnels stay a steady 60 to 66 degrees Fahrenheit year-round. Along the route, visitors see old tools, pottery shards, even a rusted first aid kit.

One massive hall, built in the 1940s, once held a water reservoir. Another space, the Rathaus-Keller, was clearly a wine cellar. Its walls are spotted with black mold from the fermentation process.

That same room is now a venue. People rent it for weddings and choir rehearsals. Its acoustics are perfect. On Halloween, it transforms into a spooky haunted house for local children.

A Unique Treasure

Other wine regions have underground cellars. But Oppenheim’s system stands apart. It’s one of the most complex in Europe. And the only one like it in Germany.

“These tunnels will still be here in 500 years,” Hilpke predicts.

Oppenheim’s tunnels have served many roles—cellars, hiding places, and community spaces. They tell stories of prosperity, survival, and surprise.

The only mystery that remains is this: will they be forgotten once more?

Our Visitor

Users Today : 69

Users Today : 69